In the 1840s, French optician and daguerreotypist Noël-Marie Paymal Lerebours published ”Excursions daguerriennes”, the first large-scale effort to reproduce photographs of the world’s monuments. Since daguerreotypes could not be directly printed, the images were redrawn and engraved as aquatints, marking a turning point in both style and perceptions of reality.

Lerebours equipped travelers—including Horace Vernet, Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet, and Pierre-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière—with cameras and chemicals to record landmarks across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. Their photographs of Giza and Alexandria represent the earliest images of these places, including the first known photograph of Egypt in 1839.

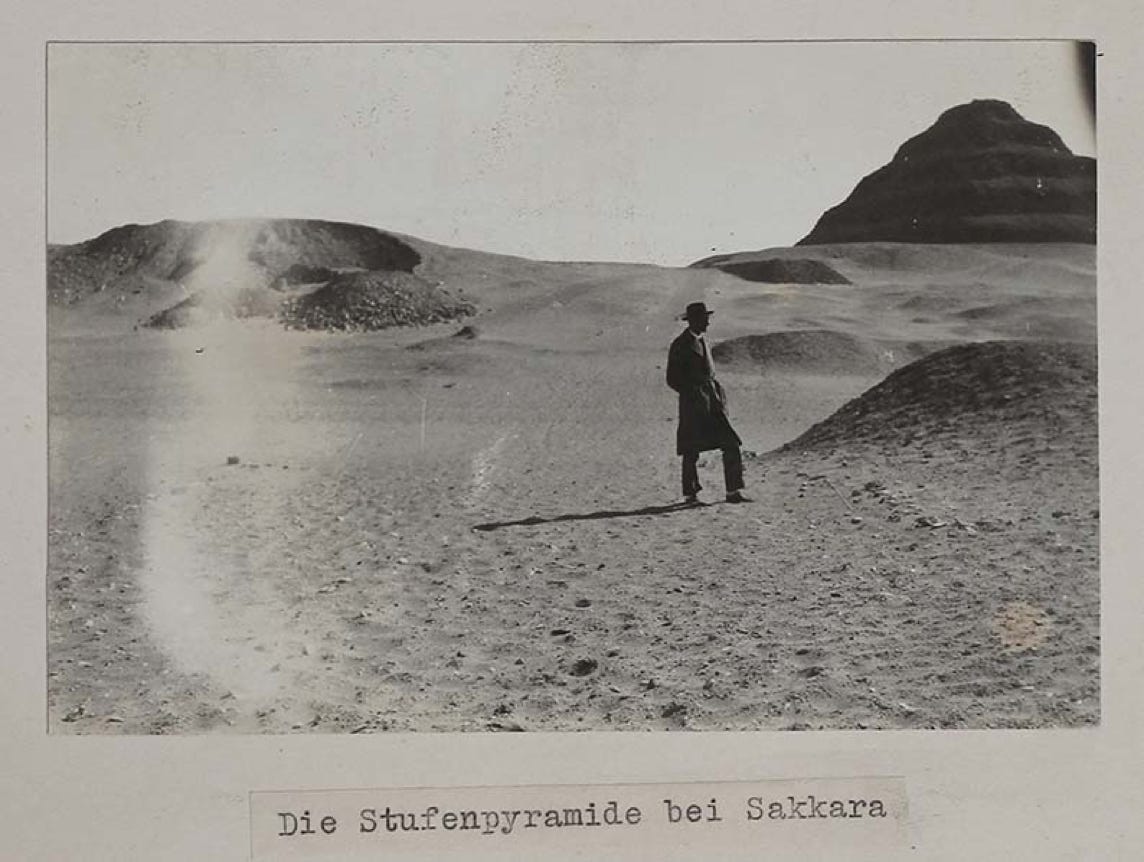

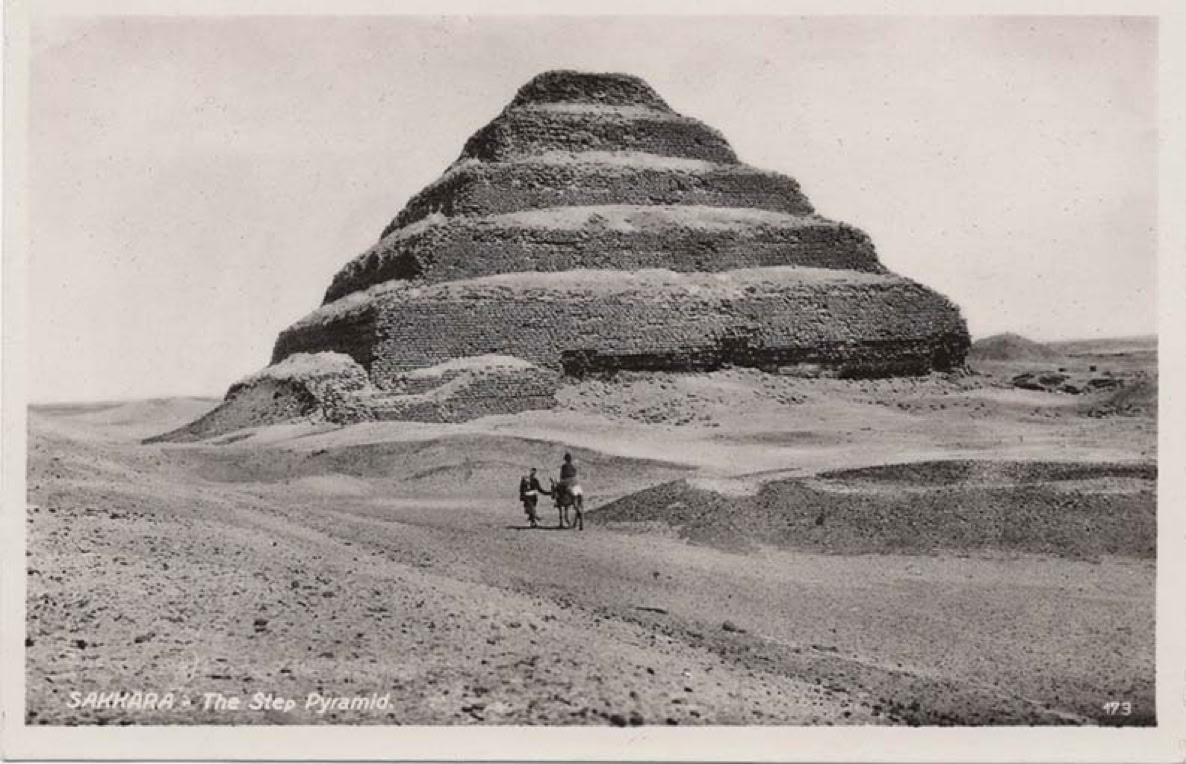

The photographers themselves were not named in the captions of ”Excursions daguerriennes.” The captions typically listed “Daguerreotype Lerebours” on the left, the printer in the center, and the engraver on the right. For the first time in history, topographical views were reproduced and widely disseminated on the basis of photographic images. Coming to Egypt two years after Vernet and Goupil-Fesquet, Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey spent several years making more than 800 daguerreotypes of monuments throughout the eastern Mediterranean. The wealthy Parisian optician Noël-Marie Paymal Lerebours equipped a handful of amateurs with cameras and chemicals. In addition, he offered a commission to the Orientalist painter Horace Vernet, director the French Academy in Rome, and his nephew Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet—the latter to make photographs to complement his uncle’s sketches. The two traveled to Marseille and departed for Egypt on October 21, 1839. Swiss-born daguerreotypist Pierre-Gaspard Gustave Joly de Lotbinière (1789–1865), went to Egypt the same year where he photographed the monuments, including the pyramids. In an entry of his diary dated November 1839 he writes: ”View of the Great Pyramids of Cheops at Gizeh. … My darkroom was placed at 320 meters from the pyramid and to the south. I gave it 9 minutes at noon. Very bright day.” (Perez 1988: 182). Also following in the footsteps of Vernet and Goupil-Fesquet was Alphonse-Eugène-Jules Itier (1805–1877), another daguerreotypist who traveled to document world treasures in the early 1840s. His travels took him to Africa, the West Indies, China, the Pacific Islands, Borneo, Manila—and Egypt, where in the winter of 184 –1846 he took one of the earliest images of Egypt that have survived up to the present..

Daguerreotypists raced to capture the world’s wonders with their new medium. Egypt was among their first and most desired destinations—along with Greece and Rome.

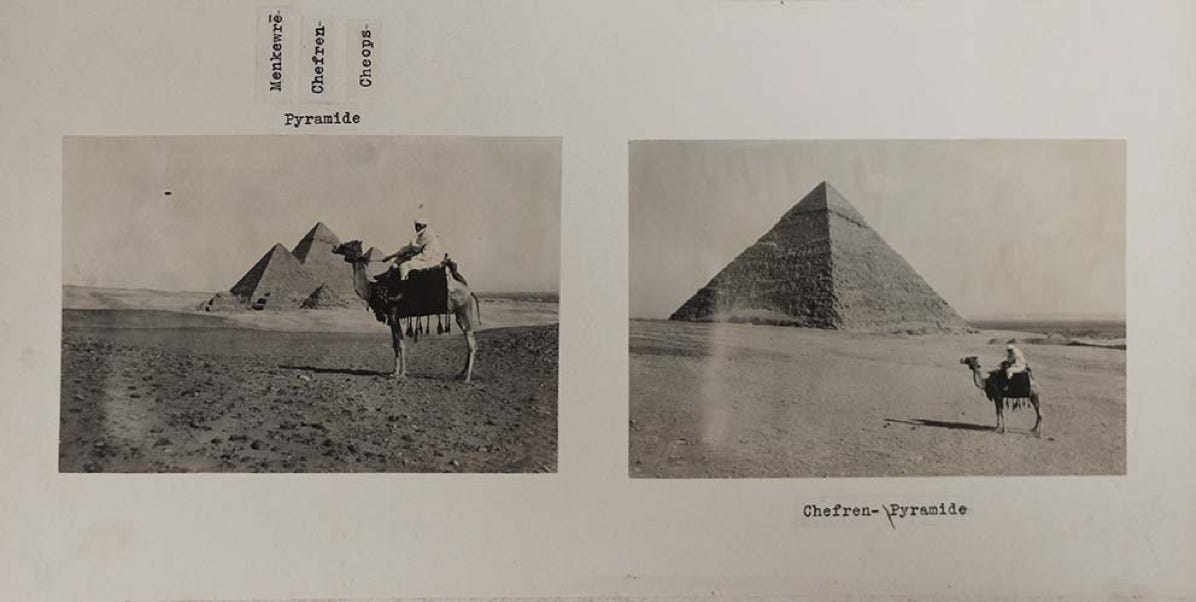

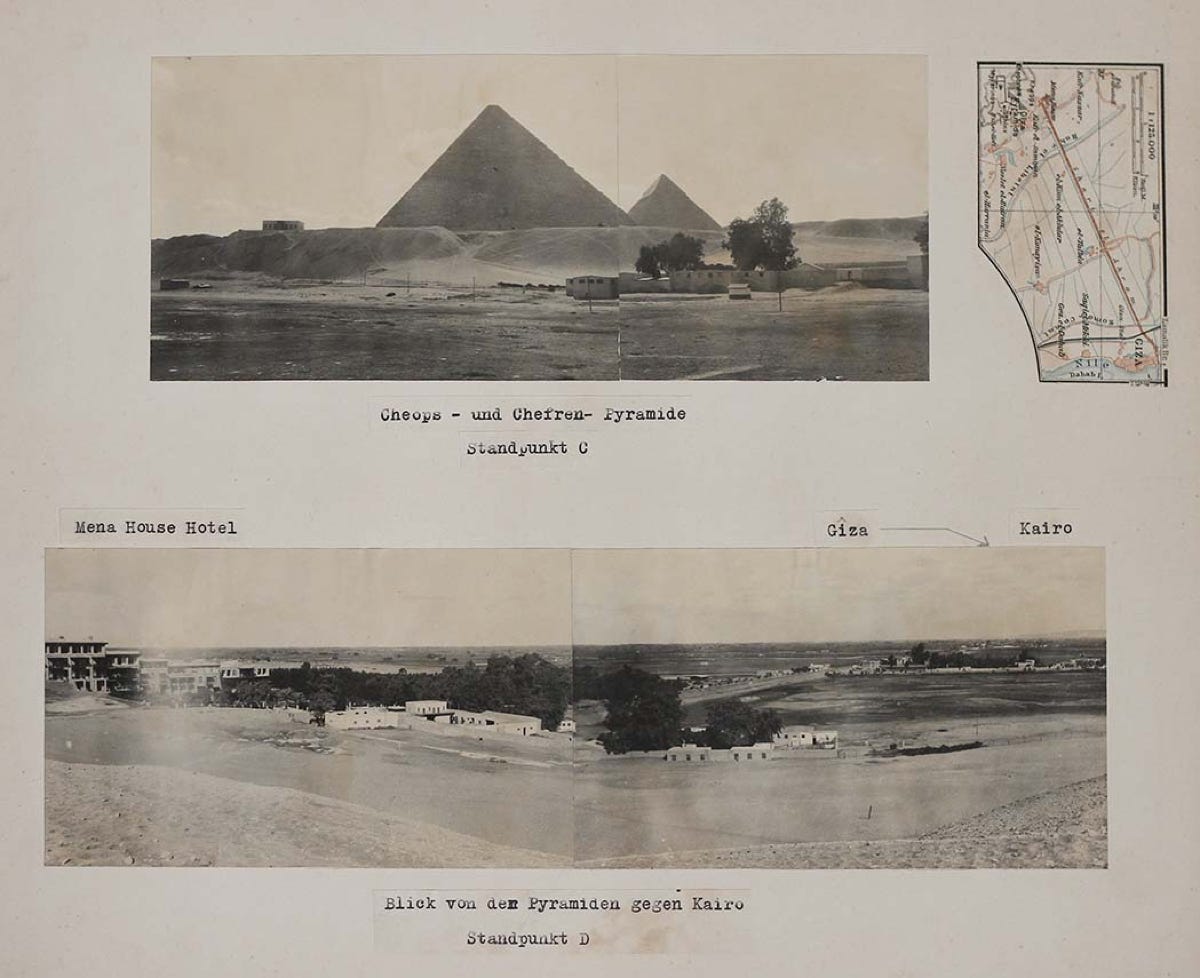

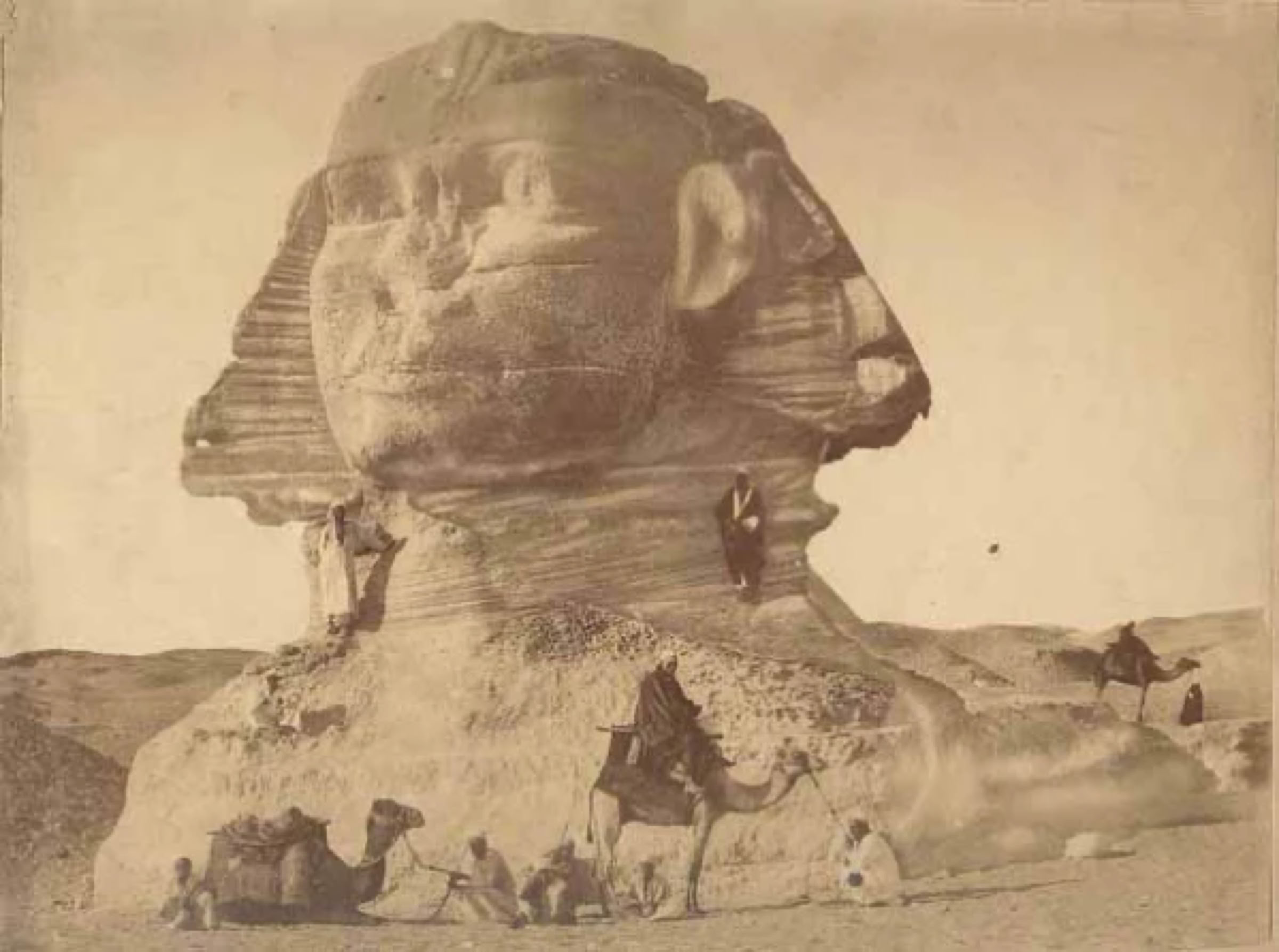

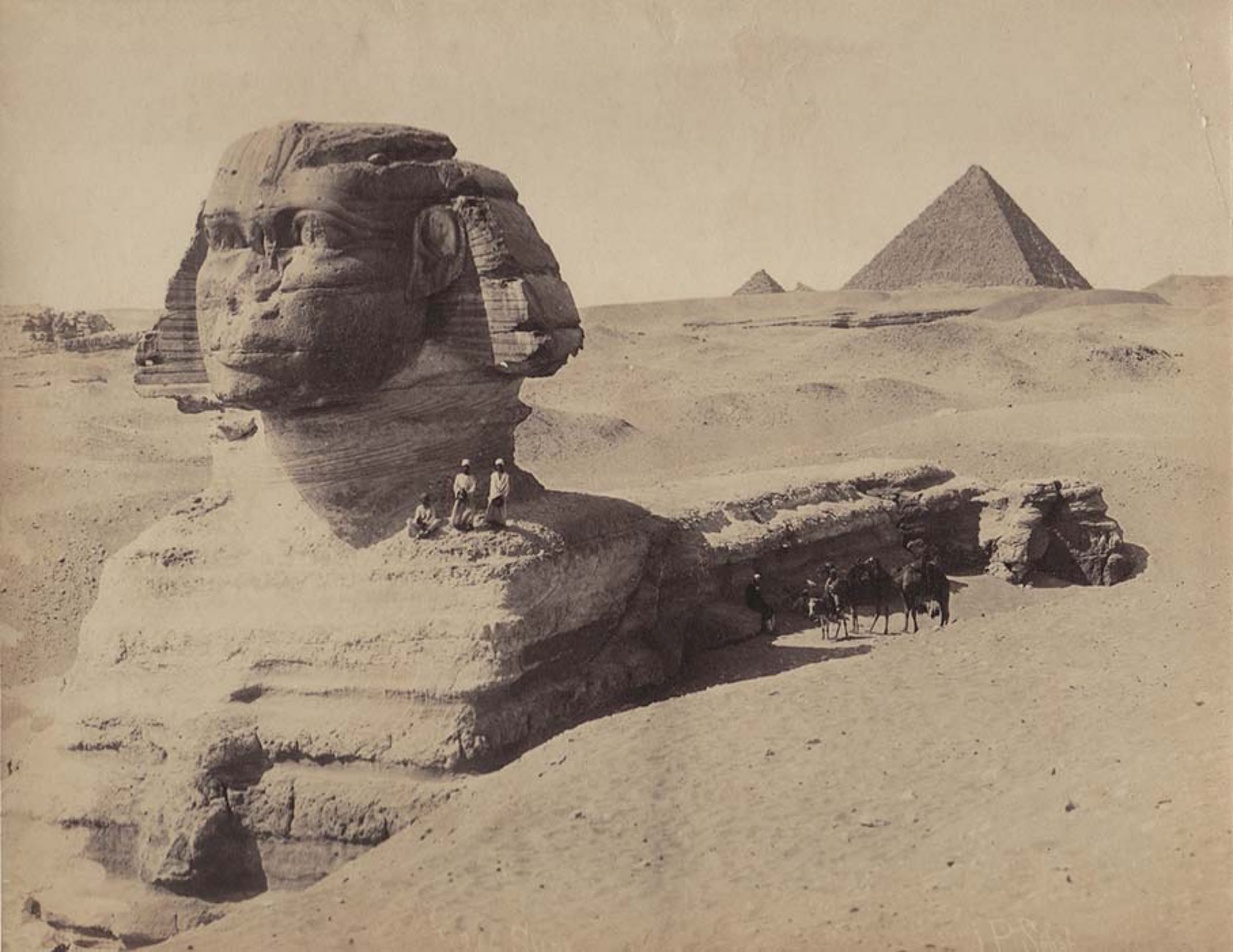

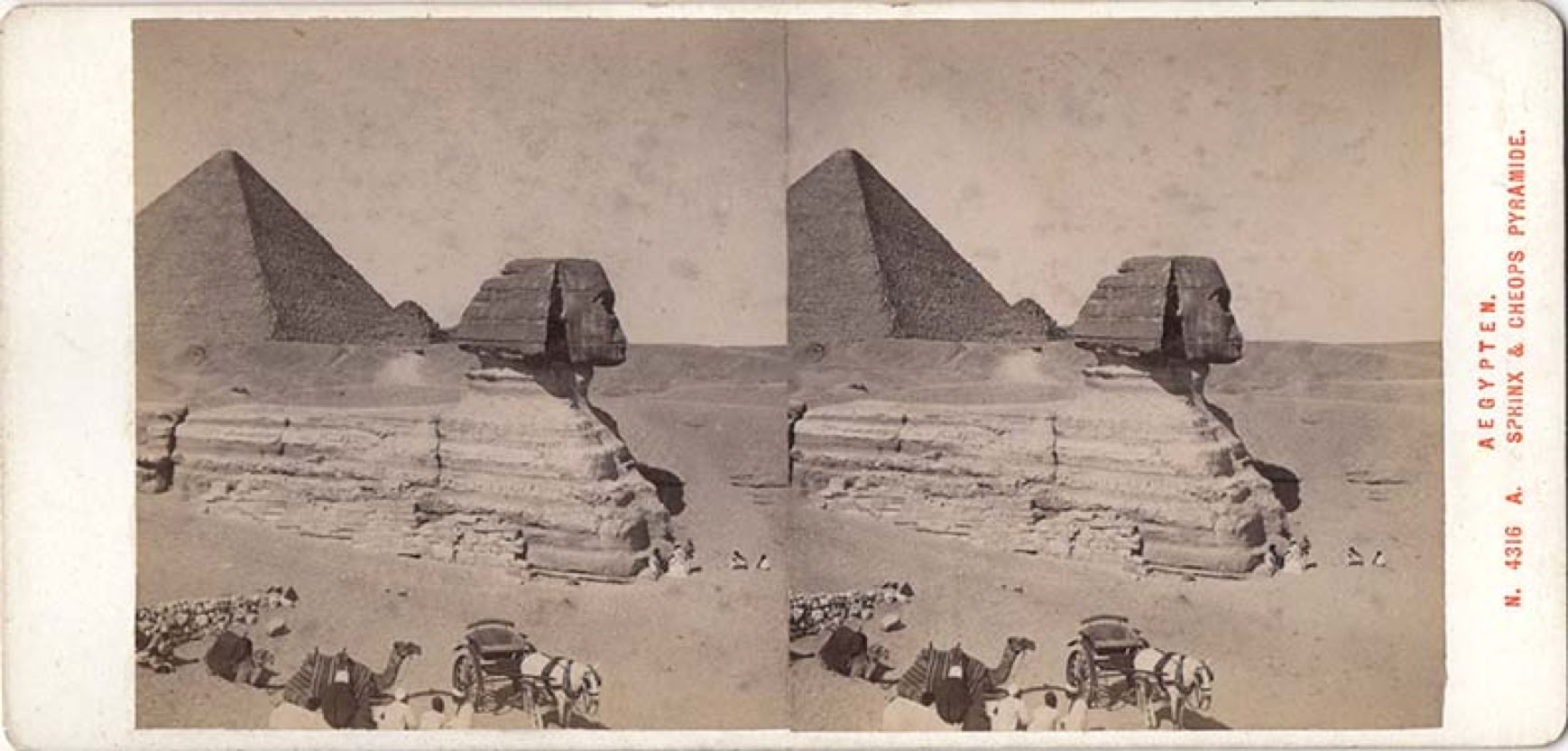

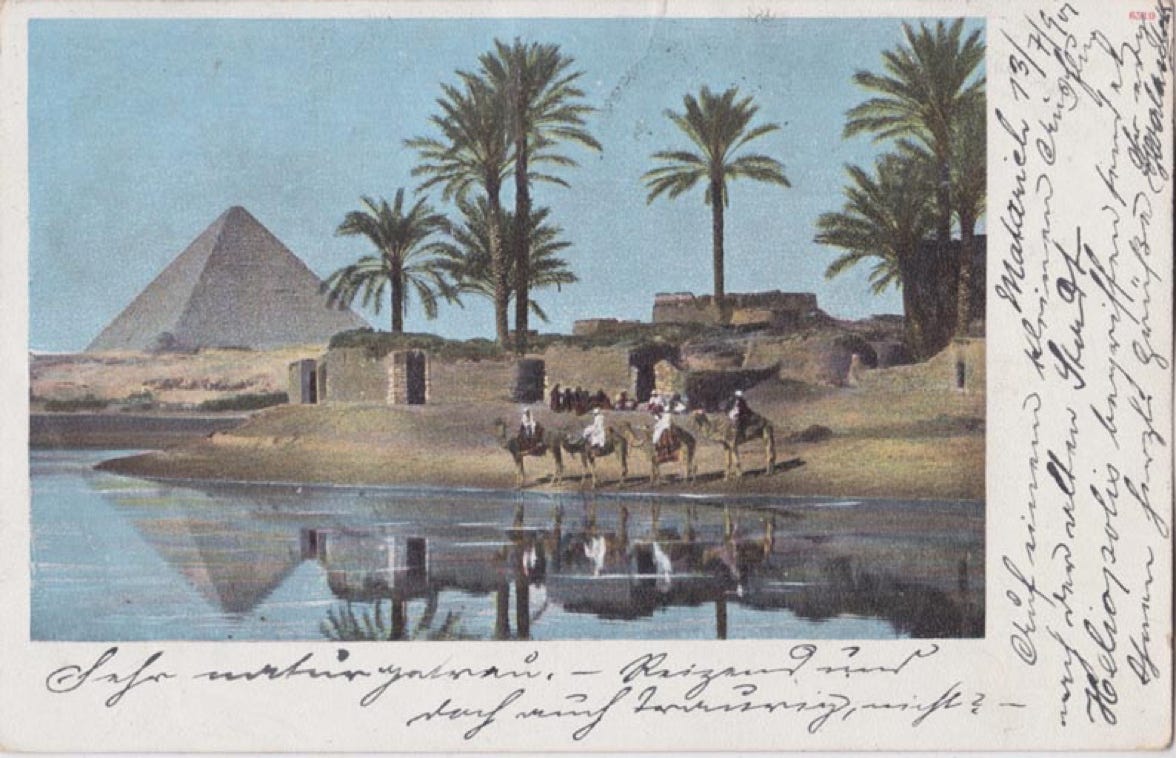

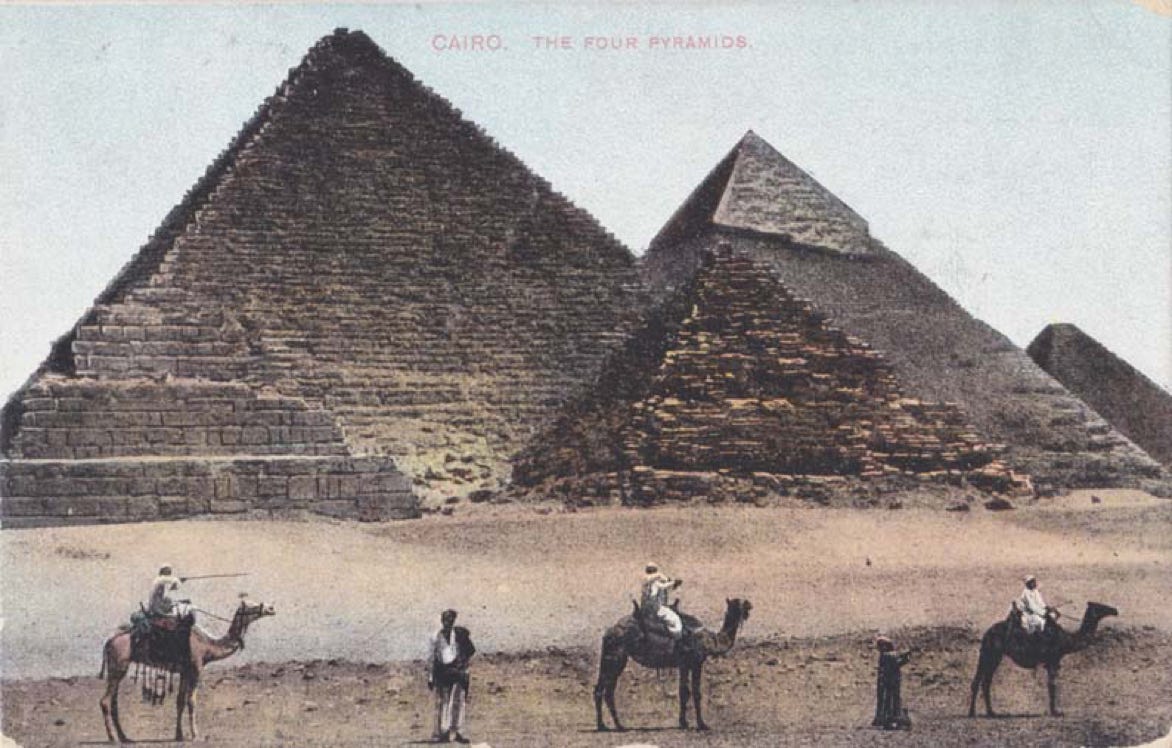

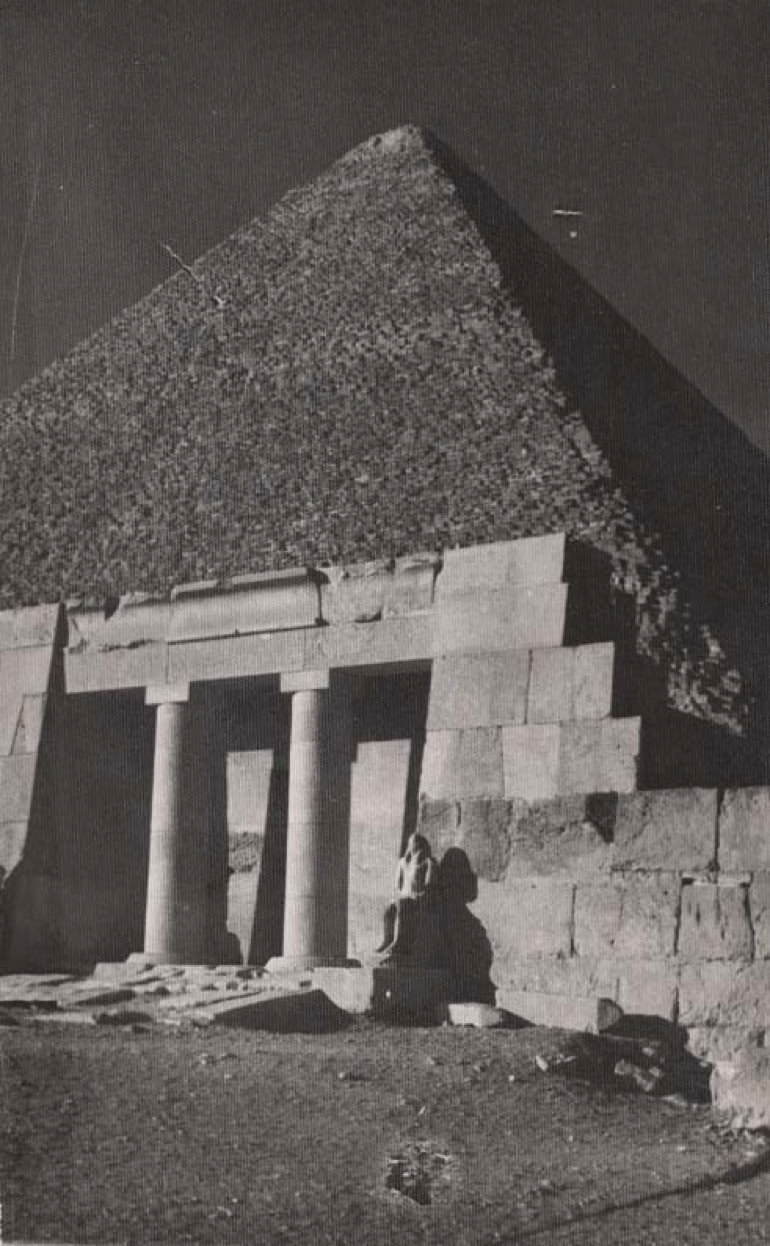

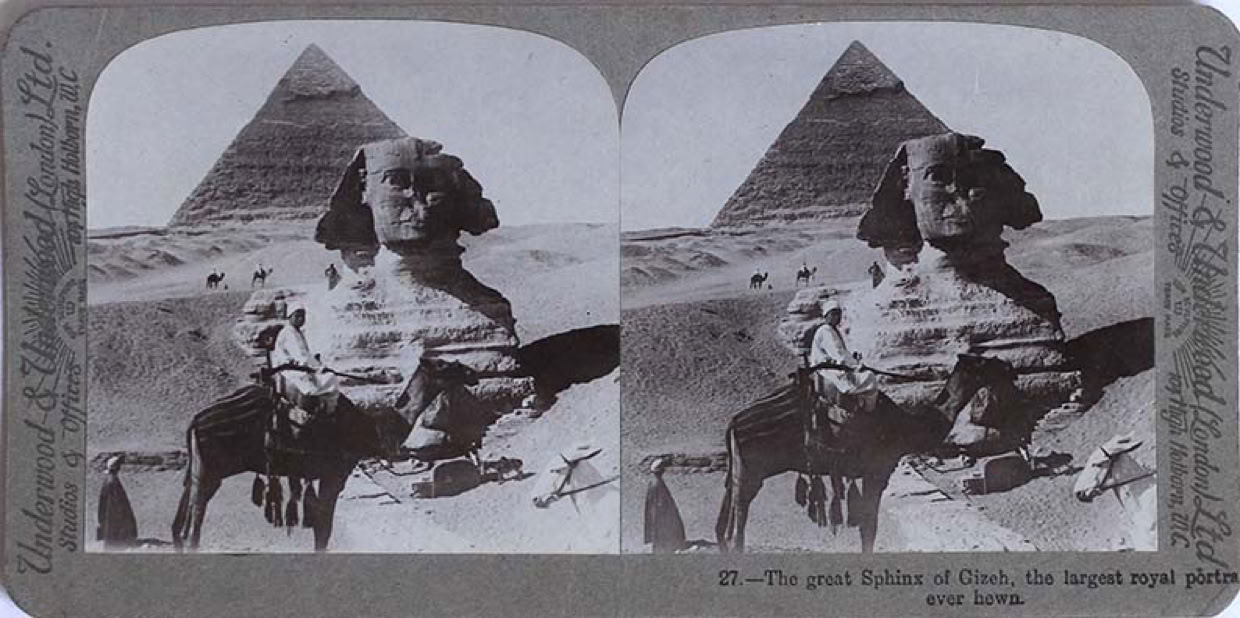

Egypt, it turned out, was an excellent place to work as a daguerreotypist, especially in the cool of winter. It offered photographers good and ample light, which was important for the long exposures daguerreotypes required. Most importantly, it had an abundance of historical places of the highest public interest to capture. Other photographers were not long in arriving. That November, Vernet and Goupil-Fesquet met another daguerreotypist in Alexandria, Pierre Joly de Lotbinière. Caught up in “daugerreotypomania,” he, too, had secured a commission (as well as equipment) from Lerebours. Soon after meeting, the three daguerreotypists made their way south to the splendors of Cairo. “We have been daguerreotyping like lions,” Vernet wrote to a friend. The trio arrived in neighboring Giza to photograph the Sphinx on the same November day. There were just two cameras in all of Egypt, and the photographer behind each was jockeying for the best angle of the same famously enigmatic antiquity.( https://www.aramcoworld.com/articles/2015/capturing-the-light-of-the-nile-egypts-first-photographs). On November 20, Goupil-Fesquet captured another iconic monument, the Pyramid of Cheops, working from outside a gate that surrounded the complex. The scene, which is known today only through a subsequent engraving is bucolic, with a saddled camel and three people quietly lounging in the foreground, the pyramid rising behind it in brilliant light. The exposure took 15 minutes.

The first paper photographs of the pyramids and the Sphinx appear to have been taken in 1849 by the French writer and amateur photographer Maxime du Camp. Traveling with his friend, the novelist Gustave Flaubert, Du Camp documented their journey with a camera for the first time. He returned with more than 200 paper negatives, which were published in 1852.

Félix Teynard (1817–1892), a civil engineer from Grenoble, followed in 1851–1852, traveling up the Nile and recording the landscapes and monuments of Egypt and Nubia. His waxed-paper negatives were printed at Élisabeth Hubert de Fonteny’s establishment in 1853–1854 and later published by Adolphe Goupil in 1858. Around the same time, John Beasley Greene—a French-American student of Gustave Le Gray—completed a series of photographs of Egyptian archaeological sites, including the pyramids and the Sphinx. James Robertson (1813–1888) and Felice Beato (1832–1909) were also active in Egypt during these years, though the dating of their photographs remains uncertain.

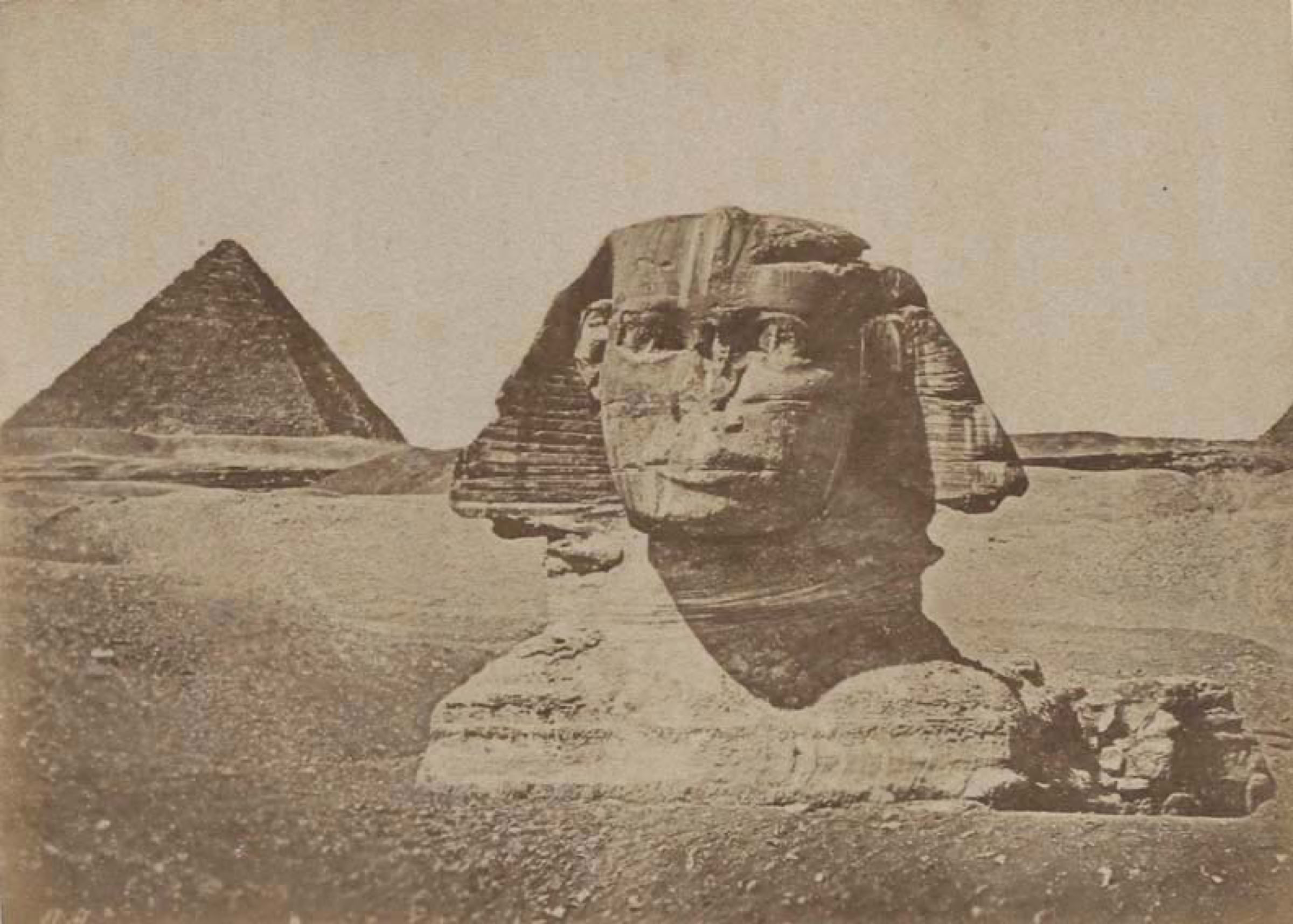

One of the most significant bodies of early work was produced by British photographer Francis Frith (1822–1898), who undertook three tours of Egypt beginning in 1856. Using an 8 × 10 inch camera, he produced wet-collodion negatives measuring 9 × 7 inches. A selection was published in 1858. By the late 1850s, more photographers were arriving in Egypt. Jakob August Lorent (1813–1884), a German-American who had first visited Egypt in 1842, made a striking photograph of the pyramids dominated by the face of the Sphinx around 1859–1860. France’s most renowned photographer, Gustave Le Gray, settled in Cairo in 1864, where he supported himself as a drawing teacher and maintained a small photography shop. From his late career in Egypt (he died in Cairo in 1884), about 50 albumen prints survive, including views of the pyramids at Giza taken between 1865 and 1869.

Many others soon followed: J. Pascal Sébah (Turkish, 1823–1886), Luigi Fiorillo (Italian, 1847?–1898), Hippolyte Arnoux (French, active ca. 1860–1890), the Zangaki Brothers (Greek), and the Armenian painter-photographer Gabriel Lekegian (1853–c.1920), among others.

Unlike other early travel destinations, photographing the pyramids was relatively straightforward: Egypt offered excellent light, a dry climate (albeit with heat and dust), and monumental forms well suited to the cumbersome photographic process, which required fragile glass plates and long exposure times. Even so, Frith remarked on the discomforts of working in a “smothering little tent” with collodion bubbling on the glass. He also noted the compositional challenges of photographing such massive structures.

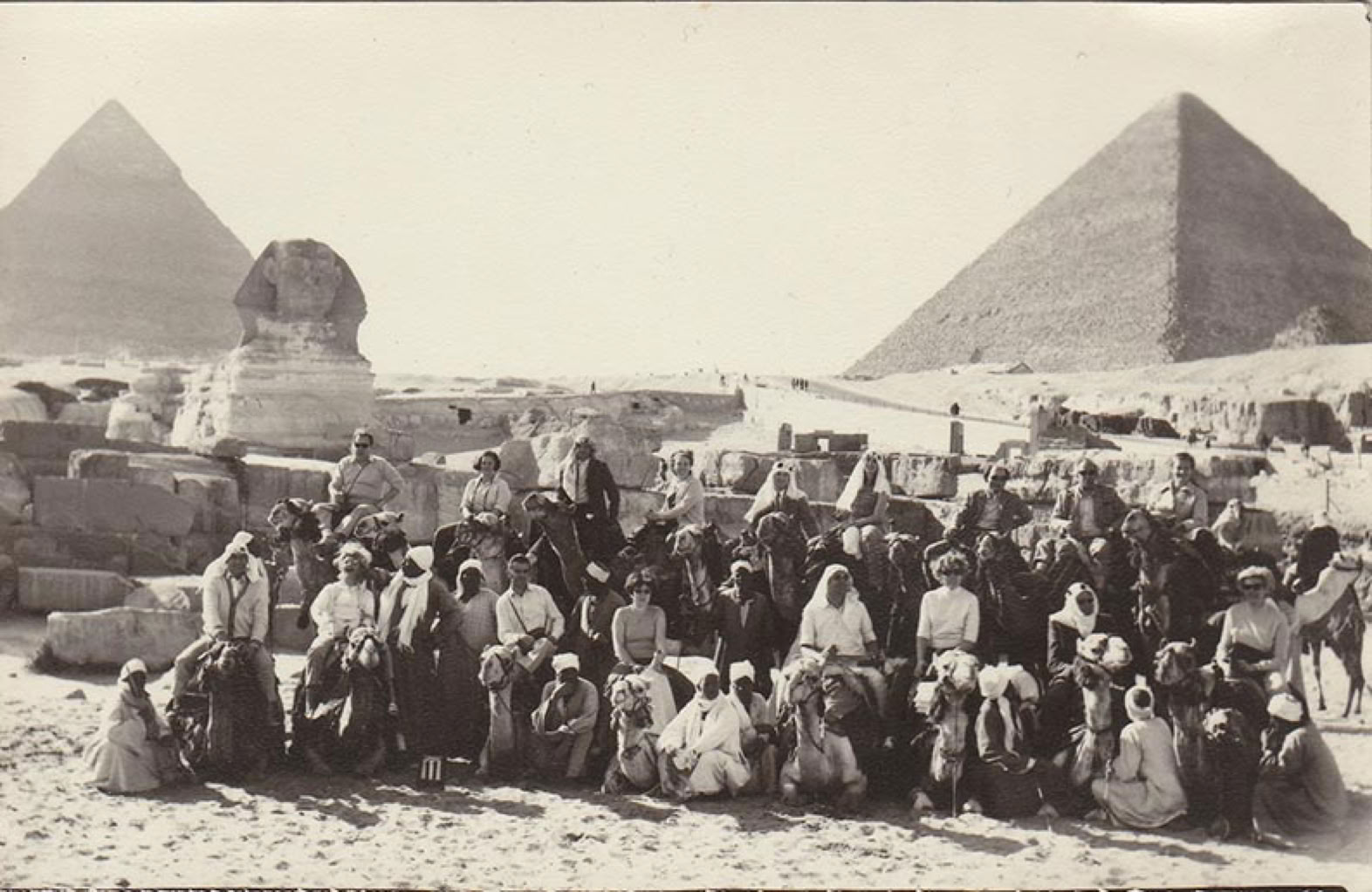

Significantly, the earliest photographs of Egyptian antiquities rarely included people. Although blurred figures occasionally appear, exposure times of less than one minute would have allowed still individuals to be captured. The omission was intentional: early photographers were interested in the monuments themselves, not the local population. Only later did figures appear, at first as human scale-markers beside colossal ruins, and eventually as subjects in their own right—residents posed before their homes, or glimpses of village life alongside ancient stone.